In the face of the new European citizens, Europe falls short on diversity

Every year the statistical office of the European Union “Eurostat” publishes statistical data on the acquisition of citizenship across its 28 Member States.

In 2016, a total of 994.800 people obtained citizenship of a Member State of the European Union (from 841.000 in 2015 and 889.000 in 2014), most of which were citizens of non-EU countries. Compared to last year, this increase of 18% comes after two consecutive years of decrease, with the main contribution to the EU-level increase coming from Spain (+36.600), followed by the United Kingdom (+31.400), Italy (+23.600), Greece (+19.300) and Sweden (+12,300).

Observing the broader statistical data, we can see that in 2016, 87% of the citizens who acquired the citizenship of an EU Member State were third-country nationals. Moroccans accounted for the largest number (101.300, of which 89% obtained citizenship of Spain, Italy or France) followed by Albanians (67.500, 97% of which obtained citizenship of Italy or Greece), Indians (41.700, 60% of whom received British citizenship), Pakistanis (32.900 of whom more than half received British citizenship), and Turks (32.800, more than half of whom acquired German citizenship). Romanians (29.700) and Poles (19.800) were the two largest groups of EU citizens who acquired the nationality of another member state.

Considering the growing support for xenophobic views across EU member-state countries (the latest Hungarian elections serve as a prime example), and since most EU member state citizenships were acquired by young people (40% were under the age of 25 and another 40% in the age group of 25-44), the question is how will Europe respond to the inevitable changing makeup of the European citizen today.

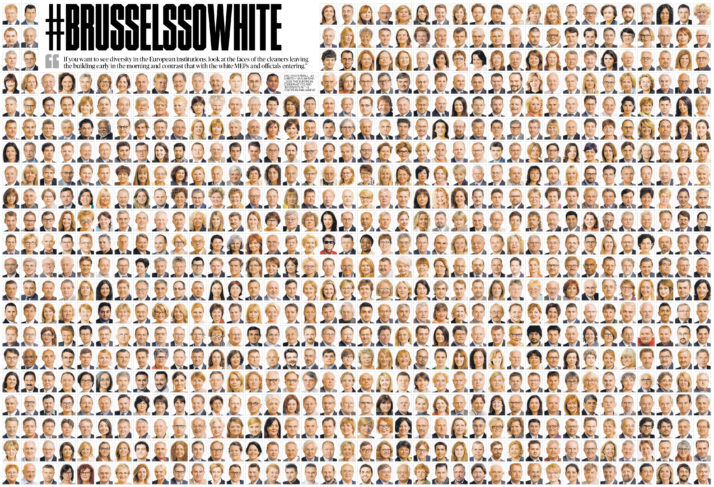

So far, the response is bleak. From a representational perspective, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity within EU institutions is striking. It is estimated that those with a minority ethnic background make up just around 1% of the population employed within EU institutions. Although no official statistics are held because statistics on race in Europe are hard to come by, within the European parliament, out of the 776 MEPs elected in 2014, fewer than 20 are thought to be from a minority ethnic background. But look at who cleans the halls of these institutions- you’ll struggle to find a white face.

What is more, when it comes to creating the policies to allow for a more diverse workforce the Commission comes up short. A recent initiative of creating policies to diversify the internal workforce of the European Commission has been met with criticism of lacking the very thing it is being created for. The European Network Against Racism (ENAR), the only pan-European anti-racist network has published extensively on this.

Moving on to issues of discrimination against minorities in the EU, the realities are also bleak for those of migrant background. According to a report released in 2017 by the Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) nearly 40 percent of respondents reported having faced discrimination in the last five years, with respondents pointing to their skin colour and their first or last names as grounds of discrimination in all areas of life, particularly however when it comes to employment. Read here ENAR’s extensive report on discrimination in employment.

Considering these statistics, the question remains; in light of the realities of the new European citizen today, is Europe ready to commit, socially and economically to its racial, ethnic and religious makeup?

Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά