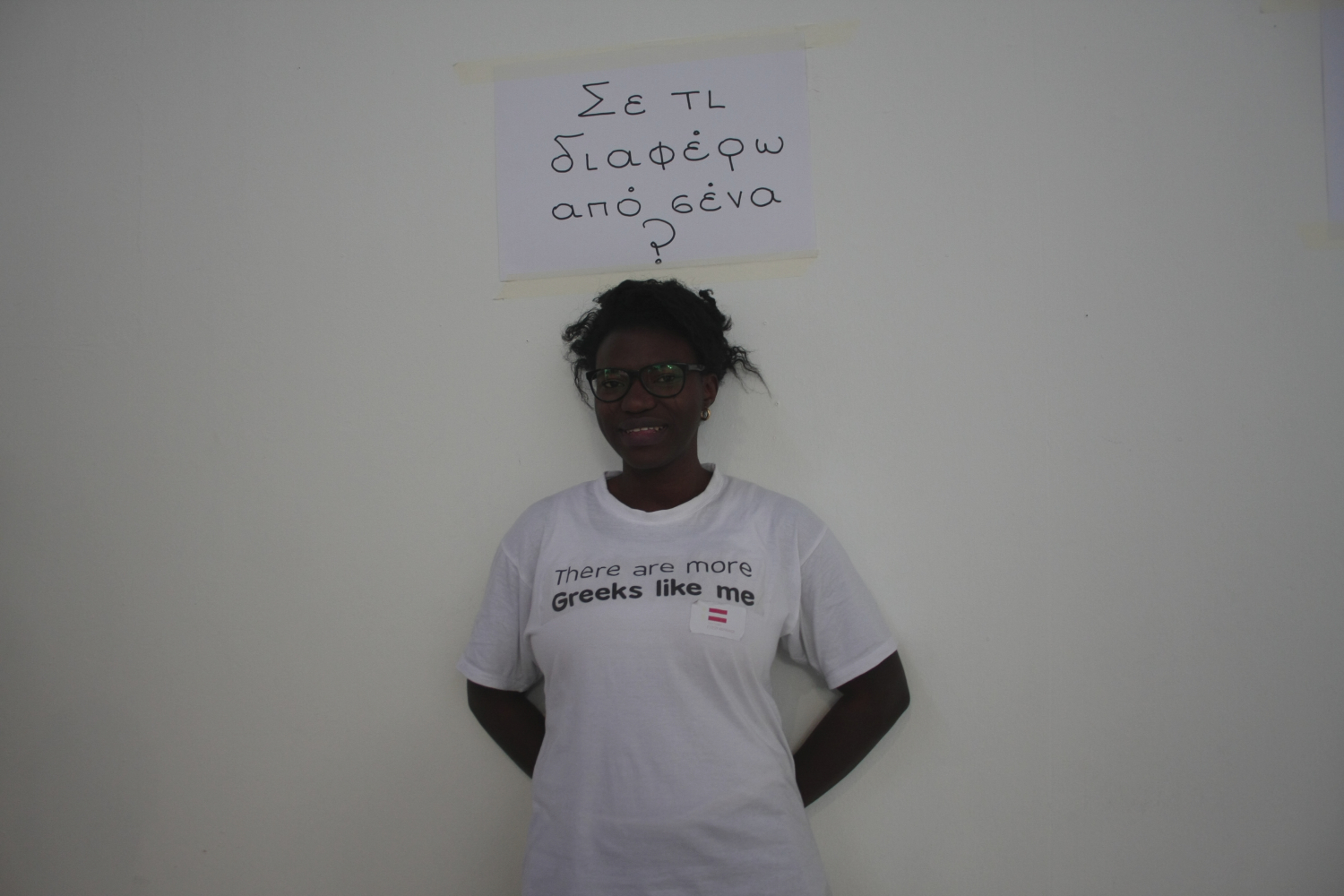

I want to be whatever I choose to be

By Nikos Odubitan

My parents came in Greece from Lagos of Nigeria in the late 1970s to study. My father studied law and my mother economics. I was born in 1981 in Athens. I was brought up and went to school in Patisia. My parents thought school was of great importance. They wanted me to definitely go to university and study like they did.

I had a carefree childhood. This doesn’t mean there weren’t any difficulties, but my parents were young, they had come to study, they had the willingness to work and create. But the reality today is different. Few Africans come to study, most of them are economic migrants or refugees and face much more difficulties.

In the house we were speaking Yoruba, English and Greek. I speak those 3 languages with the same fluency. My parents considered it was very important to be integrated in the Greek society, but at the same time not to lose my roots. My culture and my mentality is Greek. The same time I have elements from my parents’ culture. I do not know how to explain it, but this brings me to a balance, mentally and emotionally.

Many times the words “integration” and “assimilation” are confused. This is obvious in the official state rhetoric, which may talk about integration, but in reality it means assimilation. For this particular reason, many children of migrant origin were assimilated, because their cultural diversity was considered an obstacle in their being integrated in the social web.

In elementary school, and always in terms of school, the color of my skin didn’t seem to affect negatively my daily life. In high school, I felt for the first time my inner balance to be shattered. Children with migrant origins often need to “prove” – first to themselves and then to their classmates – that they are “one of them”, in order to be accepted in the new school environment. I had two classmates who could not speak Greek very well, even though their parents were Greek. Chris, who was born in Albania and Gus who was born in America. They both came to our school in high school, when they came in Greece with their family. Chris was considered by everyone “the Albanian” with whom nobody wanted to hang out. But Gus was American and everyone wanted to be his friend. All three of us were the “different” ones, either as superiority, or as inferiority.

One day I was stopped in the street. I was asked for my papers. I didn’t have any. All of my friends showed their identities. I showed nothing. I went home upset. “What do I have to show when they ask for my papers?”, I asked my parents. They did not know what to answer. The only thing I could have on me was the birth certificate from the maternity clinic “Alexandra”. That was my identity.

When I became 18, I was obligated to have a residence permit. I needed a residence permit to stay legally in the country where I was born and raised. I had never thought that I belonged anywhere else rather than in the Greek society. I was treated as a member of this society both by my friends and my social environment. And that is the answer I give to everyone who asks me what I feel.

It is my unconditional right to be a citizen of the country I was born in and raised, as it is my right to be Panathinaikos, to hear rock music, to be vegetarian and everything else I choose to be. Everyone has the right to diversity, because in the end, how many out of the 10.8 million who live in Greece today are identical?

A lot of people in Greece today consider diversity – cultural, religious, racial, gender, national – as an inferiority in our days. It does take only an extremist of the right party to endorse such beliefs. The conviction of diversity exists in every part of the Greek society, consciously, unconsciously or subconsciously. If there is a true reason for all these acts of raw violence, it is the inaction and the tolerance shown by the state to those incidents, something we can consider as an unspoken consensus by a big part of the society. I cannot believe that today, in 2013, mixed couples, mixed families, mixed companies are being targeted. I cannot believe that there are children who are beaten up at school by their classmates just because they are different. Greek society has yet to react to these actions, but I really want to believe that this doesn’t mean they accept it.

The different person today becomes a target in his/her job, in school, in the streets. He/she becomes the scapegoat of all the problems that Greek society faces during the crisis. A crisis which, as proven day by day, is not only economical.

Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά